It’s easy to lose sight of how remarkable a $17 toaster is. By just typing “toaster” into any major eCommerce site, you’ll find thousands of options, from hundreds of brands — many of which cost less than a single hour of the average American’s pay.

This wasn’t always the case. In the 1930s, the average worker would have put in almost 22 hours of labor to afford a toaster — with a common hourly pay of $0.45 and a toaster priced at $9.95 (equivalent to around $180 in today’s money). More than that, consumers of the 1930s had far fewer brands, functions, and styles to choose from, and they certainly couldn’t enjoy the ease of online shopping with same-day delivery.

And that begs the question: what makes a $17 toaster possible? While this may seem like the least of our concerns in the face of COVID-19, the very system that makes toasters so affordable also plays a role in our inability to keep the shelves stocked with the products consumers need most.

How Just-in-Time Production Changed Everything

Despite the simplicity of what it does, building a toaster from scratch isn’t easy, cheap, or efficient. Just ask Thomas Thwaites, whose journey to create his own toaster involved smelting iron in a homemade furnace, foraging for his own plastic, mining mica, and processing nickel all to create a hideous product that only worked for 5 seconds. Overall, it cost him $1837.36, and it took him nine months.

While no one really treats the Thwaites method as a viable alternative to purchasing appliances, his point is clear: what looks to be a simple $17 toaster, perhaps something you or I could make if we put our minds to it, is only made possible by a carefully orchestrated local and global supply chain system.

Manufacturers have been streamlining this supply chain since the 1930s, beginning, most notably, with the creation of just-in-time manufacturing, first seen in the “Toyota Production System” (TPS). TPS would eventually find a broader application, known as “lean manufacturing,” in the 1970s. At its heart, this is a system that optimizes every stage of manufacturing by shortening production and supply times as much as possible — and only ordering inventory for production only when it’s immediately needed.

By never holding surplus stock, lean manufacturing lets companies operate with very low inventory levels, minimizing storage costs and increasing production efficiency. Of course, to reduce the very real risk of running out of stock, highly accurate forecasts for consumer demand need to be maintained, as does constant communication with suppliers.

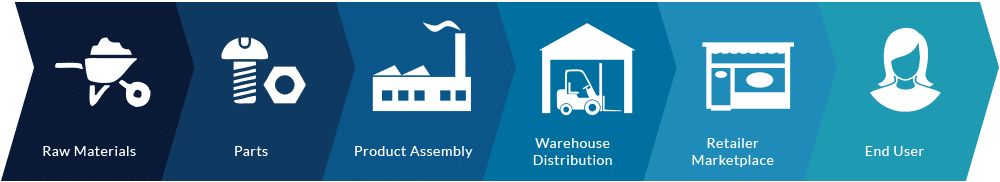

The Supply Chain is more than just manufacturing – it’s the entire system:

Raw Materials > Parts > Product Assembly > Warehouse & Distribution > Retailer & Marketplace > End-User

These supply chain efficiencies are the only way we can have our $17 toasters. It takes a lean network of suppliers, each with pipelines at full capacity, to pull it off — starting with source materials like copper, steel, and plastic, and extending to suppliers who transform them into parts and assemble them into a product. Only then, in a process that cuts out excess inventory expenses, can we drive down the production costs of kitchen appliances and pass those savings onto retailers and consumers.

In short, by using just-in-time manufacturing, automation, modern enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, and powerful eCommerce platforms such as Magento Commerce, we’ve become exceptionally good at getting everyone the toasters they want exactly when they want them.

So, why are we still exceptionally bad at supplying millions of people with life-saving supplies when they need them.

Implementing “Just-in-Case” Where it Matters

If we can get same-day delivery on our toasters, then why haven’t we harnessed the same systems to provide millions of people life-saving supplies when they need them most? To answer this, we need to look into the heart of the modern global supply chain: algorithms.

In order to drive down costs, every facet of the global supply chain must be synchronized to meet predictable consumer demands. These predictions are primarily made by algorithms — sets of rules we feed to computers that, at least in typical consumer conditions, make accurate and cost-cutting predictions. And that’s the catch: these algorithms aren’t optimized for any circumstances outside of business-as-usual.

So, when an unpredictable event occurs that changes consumer behavior, like everyone flocking to buy toilet paper and hand sanitizer, the supply chain doesn’t have the resources to meet the demand. There just isn’t enough surplus inventory. It’s been removed from the system by design.

While there won’t be any single catch-all answer to why we weren’t prepared in the face of COVID-19, we can tie some of it to a failure of preparation in the global supply chain. As it turns out, we aren’t good at predicting things that haven’t happened before (or haven’t happened in a long time) and we aren’t fond of investing funds and resources into things that might not happen. So, if we have no existing data sets, like how a major pandemic of this sort will alter the behavior of modern consumers, then we’re going to struggle to build an adequate preparation plan into our projections — if we think to at all.

We have succeeded at solving problems like this in the past — just look at how the Dust Bowl of the 1930s and the economic hardship of the 1970s led us to create a strategic grain reserve specifically for emergency food needs.

But, in this new fast-paced consumer-based economy that can supply us with a $17 toaster, what can we be doing better to store reserves of medical supplies like masks, ventilators, and pharmaceuticals as well as plenty of toilet paper? While the Strategic National Stockpile was established to collect necessary medical equipment and consumables for times of need, there’s only enough inventory to fill momentary gaps in the supply chain. What we need now is a model for adapting, predicting and responding to demand during a crisis, to supply many types of important and not-so-important products.

Building Just-in-Case Reserves into the Supply Chain

Imagine that the global supply chain is a network of hoses watering a garden. Each hose, as a supplier, is always operating at full capacity, providing the garden the right amount of water it needs in the moment. Should something unexpected happen, such as a drought, the garden will need more water than the hoses can supply. In this case, the hoses will have to ramp up production — but without any surplus available, they won’t be able to do it fast enough.

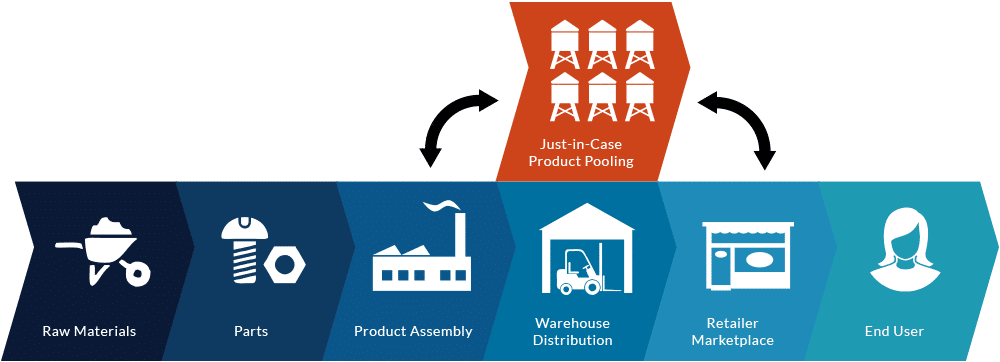

This is what leads to shortages of products like toilet paper and hand sanitizer; demand spikes and the supply chain can’t adjust. But what if we add reserves to the supply lines of the most important products? What if the hoses ran through water towers, standing by just in case conditions change?

What if we add algorithms and predictive modeling to estimate products that might be needed during dramatic shifts in consumer behavior because of crises like forest fires, hurricanes, floods and pandemics? We then apply those models to a secondary distribution and warehouse pool to include “Just-in-Case” products, where those products are kept in reserve for demand during future crises.

Just-in-Case products can be classified as “crisis products” or “crisis materials” – they would be pooled at the Warehouse Distribution phase of the supply chain. In normal times these “Just-In-Case” pools can be drawn down after certain thresholds are met.

As the pools are drawn down, inventory can be refreshed with new products (keeping products from becoming outdated). If there’s a crisis, the pooling towers could be drained to flood the market with needed products.

These wouldn’t have to be static reserves. To avoid supplies becoming outdated, we could find a way to incentivize maintaining a certain level in the reserves before refreshing them with new products, and then provide some kind of assistance to cover any overhead. Of course, the money to maintain these reserves and incentives would have to come from somewhere. In much the same way that the government intervened to set up the grain reserve and the Strategic National Stockpile, perhaps supporting Just-in-Case measures in the supply chain can be a part of a new public/private crisis management effort.

If we want to do this, we need to start with the algorithms. While the current process can keep shelves stocked in business-as-usual circumstances, we’ll need to leverage predictive algorithms to model behavior during different crisis scenarios (such as forest fires, hurricanes, pandemics, etc.) to ensure that the supply chain can adapt to dramatic shifts in consumer demand — without supply lines drying up.

And this doesn’t have to be limited to global crisis management. We could build Just-in-Case practices into our business strategies for non-crisis products too. If we missed this globally, it stands to reason that small businesses could be making the same mistake, trying to maximize efficiency in business-as-usual scenarios, at the expense of less predictable ones.

Perhaps intelligent distributors and retailers can build reserves into their ERPs and analytics so they can seamlessly meet unexpected spikes in consumer demand — even if instead of masks, it’s something like the Instant Pot, an updated version of a traditional slow-cooker that quickly became an Amazon best-seller.

Either way, even in all of the unpredictability of life, we all know that something else will come. And it’s up to us to meet that challenge head-on and set up systems capable of bringing relief to everyone who needs it — as quickly and reliably as possible.

Luckily, by leveraging existing, advanced eCommerce tools such as Magento to generate sales AND improve business planning & operations, we can take action now to be better prepared for future disruptions – both the happy surprises and the unforeseen disasters.

Get a FREE eCommerce Business Assessment – learn how you can manage orders, product data, customer information, and accounting processes in one seamless system.

April 15, 2020

All Articles